Ulrich HarbIn 1978, Reimer Verlag published the book Ilkhanidische Stalaktitengewölbe by Ulrich Harb after the German excavations at Takht-i Suleiman in northwest Iran in the 1960s. Takht-i Suleiman means "Throne of Solomon". Today it is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The book is out of stock, but available in university libraries. This webpage shows my summary, a selection of text from Harb and the illustrations. |

Summary

Harb revealed that he had been present during the German excavations at Takht-i Suleiman in northwest Iran in the 1960s. The Ilkhanid palace there dates to the final quarter of the 13th century. Harb observed the ruins firsthand and identified multiple layers of construction. He specifically studied the remnants of the vault in the Southern Octagon, suggesting it may have been built using pre-defined units.

In Chapter 4 of his work, Harb provides a detailed analysis of these units, distinguishing between prefabricated and intermediate elements. One key artifact, a gypsum plate with geometric incisions, was handed over to Harb for analysis in 1968 and became the central focus of his research.

Chapter 5 explores a broader range of Ilkhanid muqarnas vaults to better understand the assembly of stucco components at Takht-i Suleiman. Harb illustrates how various combinations of elements could have come together, ultimately leading to his reconstruction of the design found on the gypsum panel.

In Chapter 6, he presents this reconstruction. However, only in the final paragraph does he acknowledge that the dome design was purely theoretical. The dome was never built at Takht-i Suleiman, and no significant muqarnas fragments were discovered above any of the square rooms in the Ilkhanid palace. Harb suggest that his set of units is complete, but one of his final remarks is that "since the complete elements are insufficient to explain the structure of the vault, the designer of the panel must have also used partial elements, not shown explicitly, which can be inscribed within the existing surfaces."

Conclusion

- The remains in the Southern Octagon inspired Harb's ideas about prefabricated units.

- His catalog of elements was extensive enough to reconstruct the floor plan of the dome found on the gypsum plate.

- His assumptions were grounded in comparisons with contemporary Ilkhanid examples.

- Harb admits that the design of the dome on the gypsum plate might not have been built at all because there ate no physical remains in the central room.

- Important remark is that since the complete elements are insufficient to explain the structure of the vault.

Links to websites

Selection

I translated the entire text from German to English. Below is a selection of key translated sections.

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: Gypsum Plate>

- Chapter 2: On Stalactites in General

- Chapter 3: The Remains of the Vault in the Southern Octagon at Takht-I Suleiman

- Chapter 4: The Plaster Muqarnas of Takht-I Suleiman

- Chapter 5: Examples Of Ilkhanid Stalactite Vaults

- Chapter 6: The Design of the Stucco Panel from Takht-I Suleiman and its Reconstruction

Introduction

Since 1959, the Sasanian sanctuary of Adur-Gushnasp at Takht-i Suleiman has been the subject of excavations led by the German Archaeological Institute. This sanctuary, which flourished during the 5th and 6th centuries, continued to function as a Zoroastrian cult site until the 9th century-two centuries after the Islamic conquest of Persia. Only then did the site's importance begin to wane, although it was never entirely abandoned.

In the 13th century, Takht-i Suleiman experienced a resurgence in construction, largely due to its prized lake. The Ilkhan Abaqa built a summer palace here, which has since become the second main focus of archaeological research at the site. The palace was active for only a short period in the early 1270s. Soon after-and still during the Ilkhanid period-its partial demolition appears to have begun. This is evidenced by dated architectural ceramics found broken and stockpiled by the late 1280s, during the reign of Abaqa's successor, Arghun.

Additional buildings were constructed on the site, above the ancient fire temples. These are not considered part of the palace complex. Some of these structures stand atop sanctuary rooms buried under meters of debris; others incorporate the ruined walls of the older complex. During the excavation of the second fire temple, a rural homestead was uncovered in the northern area, above rooms KO I and PE. In its masonry, archaeologists discovered a gypsum plate with incised geometric designs. This slab was handed over to Harb for analysis in 1968 and became the focal point of his research.

The slab appears to be a construction sketch for an elaborate and technically complex stalactite dome. Based on its form and design, it shows close parallels to Ilkhanid vaults from the palace period. The only period in which the presence of Islamic architects at the site can be confirmed is the 1270s-the so-called "palace period."

Gypsum Plate

Note: This description is a translation of Harb's description in chapter 1.

A plaster slab measuring 47 by 50 cm and 3.5 to 4 cm thick contains a square field with a side length of 42 cm. Within this square, a geometric line pattern has been incised. The lower left corner is slightly broken off and missing. The rest of the slab is fractured into seven pieces, which - apart from a small missing fragment near the center - can be reassembled.

The pattern consists mostly of squares, rhombuses, and right isosceles triangles, arranged along the borders of the square field. The side lengths of the rhombuses and squares, as well as the legs of the triangles, are all consistently 3.5 cm. The entire layout is organized symmetrically around a diagonal axis. In the upper right corner, the design ends in a quarter of an irregular octagon. Shapes with unequal side lengths only appear along the diagonal and at the octagonal corners.

All of the angles in the design are multiples of 45 degrees (i.e., 45°, 90°, and 135°), except for the deltoids (kite shapes) and their adjoining triangles along the diagonal. The 3.5 cm segments were likely measured using a compass. While it's unclear how the horizontal, vertical, and diagonal lines were constructed, smaller compass arcs may have been used to create the 45° and 90° angles - as no other method seems apparent.

The deltoids along the central axis appear to be formed by diagonally connecting opposite corners of a regular (though irregularly arranged) hexagon. Most of the lines were probably incised using a ruler. However, in the upper diagonal section, the usually careful drawing becomes imprecise, and several lines appear to have been drawn freehand. None of the lines shared across adjacent fields were drawn in a single continuous stroke - suggesting that the design was only intended to join up to two adjacent units at most.

Beneath the clearly visible network of lines, there are multiple smudged and partially erased markings. Some of these - such as the diagonals of squares - may have served as construction lines for the final design. Others, particularly in the upper part of the slab, do not correspond to the visible geometry and likely belong to an earlier, abandoned version of the drawing. Even within the final sketch, some lines were crossed over by newer ones, and previous construction guides were not always removed.

While it's not always possible to determine the order in which the lines were incised, one thing is clear: the design was left incomplete. The construction ends abruptly at the short octagonal segment in the upper right diagonal section.

On Stalactites in General

This text is a translation of a selection of Harb's text in chapter 2.

A stalactite vault refers to a complex vaulted surface made up of numerous individual cells, each composed of partial vault forms. These mostly concave elements are arranged above and beside each other in a layered fashion, somewhat like a corbel vault, and resemble small bracket-like projections or consoles. The upper tips (apices) of these elements extend outward beyond those below them, and their top edges serve as the springing points for the next layer above. Stalactites can appear in a wide range of sizes and can be used to create almost any vaulted shape.

There is no single geometric rule that defines all stalactite forms. This distinctive architectural element-so central to Islamic architecture and celebrated for its dynamic play of light and shadow-evolved over time. What began as a structurally functional building feature gradually became a purely ornamental, three-dimensional surface. The boundary between structural purpose and the Islamic aesthetic of rich decoration is difficult to pinpoint, as the ornamental forms never violate architectural logic.

Hardly any architectural feature has remained untouched by stalactite design: squinches, pendentives, cornices, semidomes, domes, niches, portal frames, capitals, consoles, and arch intradoses all display this motif. Stalactite vaulting is found across the former Islamic world-from Spain and the Maghreb, Egypt and Sicily, through the Middle East and Arabia, all the way to India and Uzbekistan.

The Remains of the Vault in the Southern Octagon at Takht-I Suleiman

This text is a translation of a selection of Harb's text in chapter 3.

Between 1965 and 1969, excavations revealed a series of rooms from the Ilkhanid palace adjacent to the "great" (western) iwan. This area is framed to the north and south by two octagonal buildings, nearly identical in ground plan. The focus here is on the southern structure, referred to as the Southern Octagon, due to its preserved stalactite vault remains.

Described elsewhere as a kiosk, the Southern Octagon consists of an octagonal interior space with rectangular niches extending inward from each side. The triangular wall segments between the niches and the outer octagonal wall supported both the niche vaults and the central dome above.

Within the debris mound, a collapsed stalactite vault shell was discovered. It lay upside down, with its concave decorative surface facing downward, resting intact atop earlier masonry rubble. By carefully removing overlying debris and hollowing out the area below, archaeologists were able to study the vault's construction, though it could not be preserved. The squinch discovered here, likely spanning the northeastern corner of the niche, consisted of four superimposed layers of cantilevered gypsum forms, rising from a clearly defined cornice.

Additional debris above the Southern Octagon and nearby rooms yielded a large quantity of plaster muqarnas elements. However, these were all isolated pieces with no continuous or coherent sections of vaults. As a result, while countless theoretical vaults could be assembled from the available fragments, none of the original forms can be reconstructed with certainty.

Importantly, the plaster pieces were not part of the load-bearing structure. Instead, they served as temporary formwork for the supporting masonry that was cast behind or around them and later hardened in place.

The Plaster Muqarnas of Takht-I Suleiman

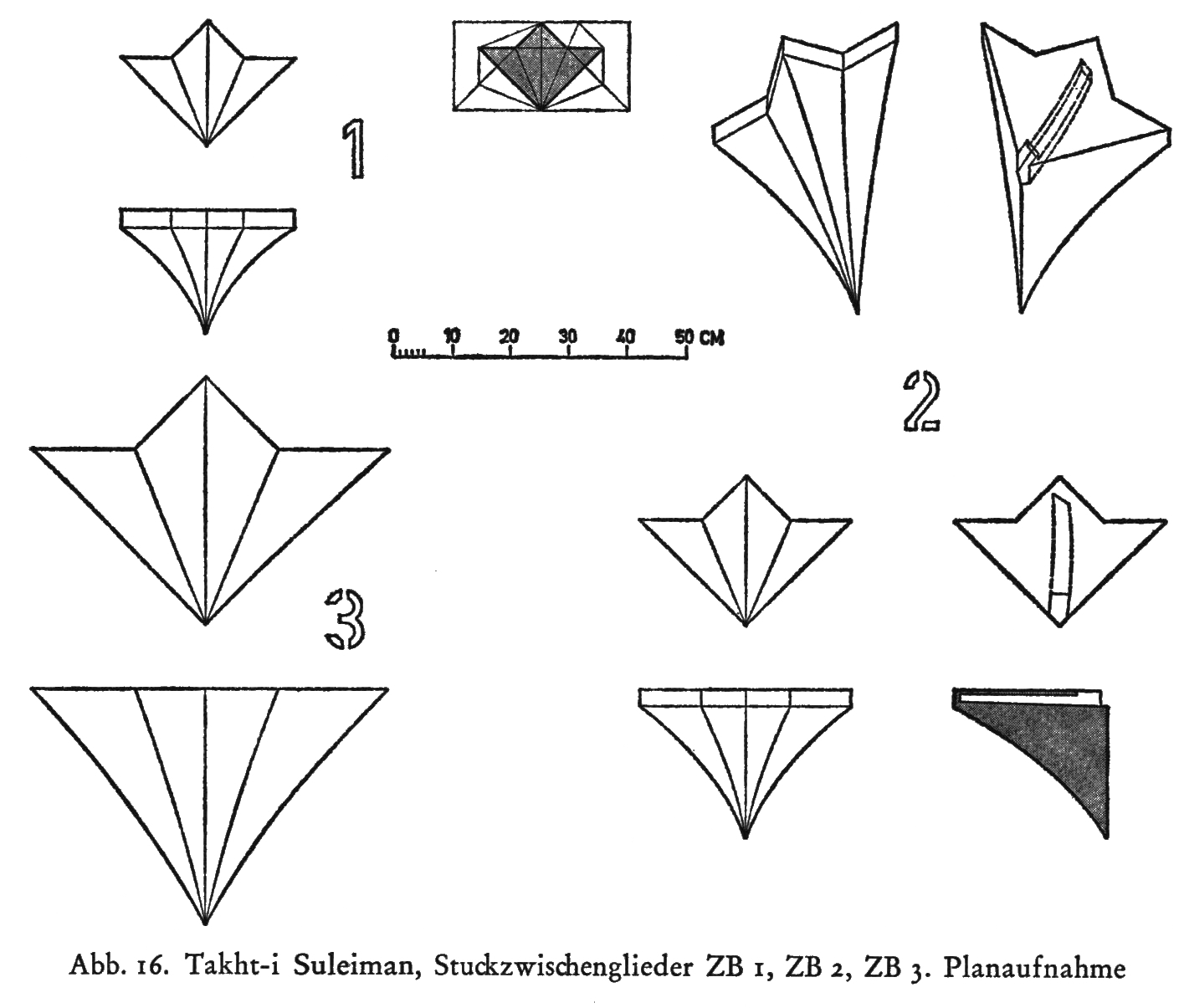

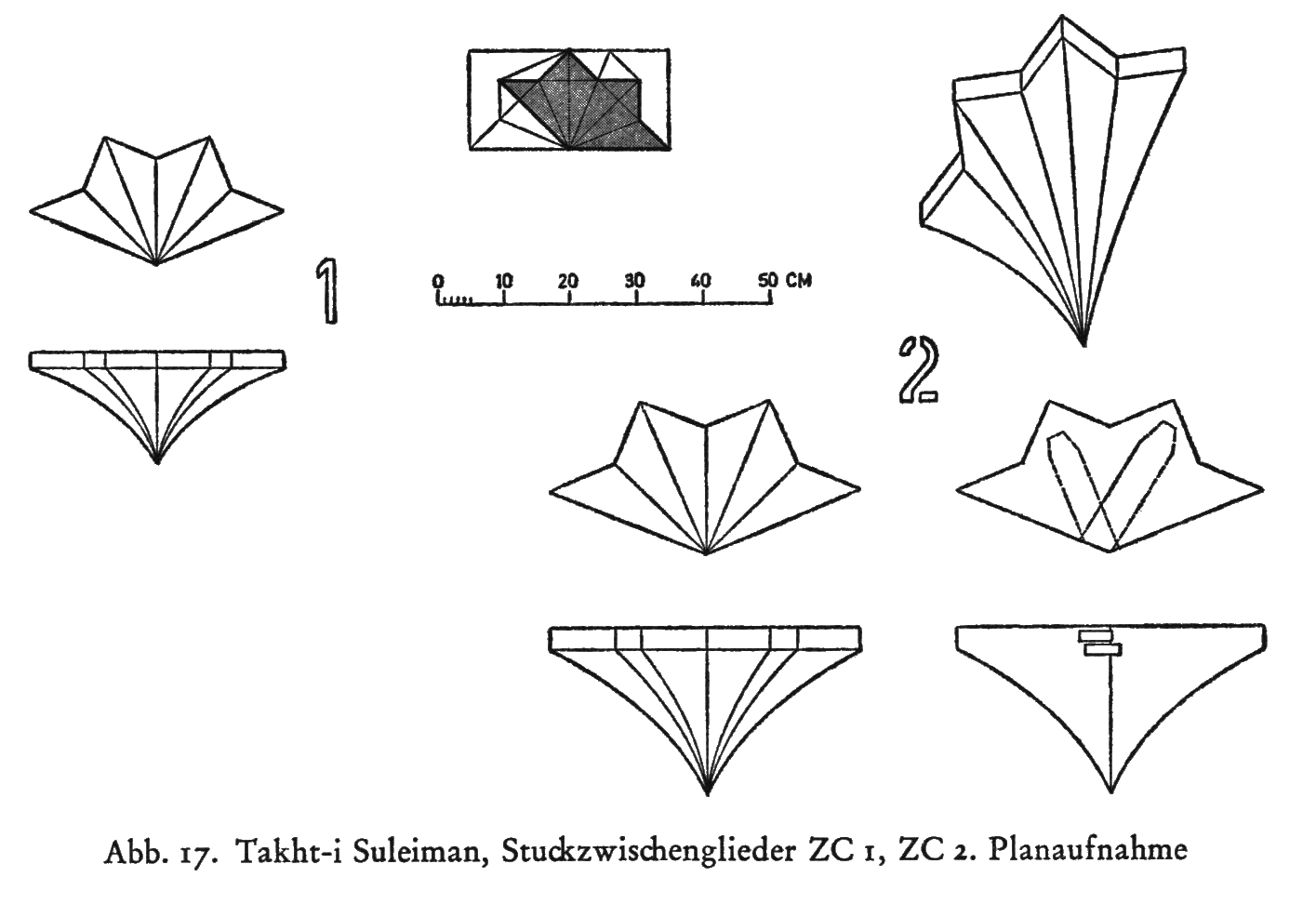

This text is a translation of a selection of Harb's text in chapter 4. See figure 4 to 15 for prefabricated stucco element FA I to FE 1.

The debris layers above the Southern Octagon and the adjoining areas yielded a large number of plaster muqarnas elements. Since only isolated pieces and no coherent parts of a vault were found, any conceivable vault shape could, in theory, be assembled from these individual pieces-but none of the original vaults can be reconstructed with certainty.

The collapsed state of the dome revealed an important structural detail: in the transition zone from the impost to the base circle of the half-dome-the area where the muqarnas were located-the heavy backing masonry had remained stable. Only the formwork elements, particularly the intermediate pieces not integrated into the masonry backing, had detached from the shell during the collapse.

The discovered stalactite (muqarnas) elements fell into three distinct size categories. Notably, all pieces feature at least two identical side lengths on their undersides-matching the side length of the square used in the auxiliary geometric construction. This single dimension is sufficient to determine the full form of each element's underside.

All of the stucco muqarnas with horizontal bearing surfaces spanned the full height of a construction layer. Their exposed undersides consistently display the same molded patterns, indicating that they were cast in molds prior to vault construction. These should therefore be regarded as prefabricated components.

Once these prefabricated elements were positioned and supported within the vault, the gaps between them were filled with intermediate pieces. The entire formwork was then backfilled using rubble stones set in gypsum mortar, completing the structure.

Examples Of Ilkhanid Stalactite Vaults

This text is a translation of a selection of Harb's text in chapter 5. See figure 20 to 34 for examples of muqarnas vaults.

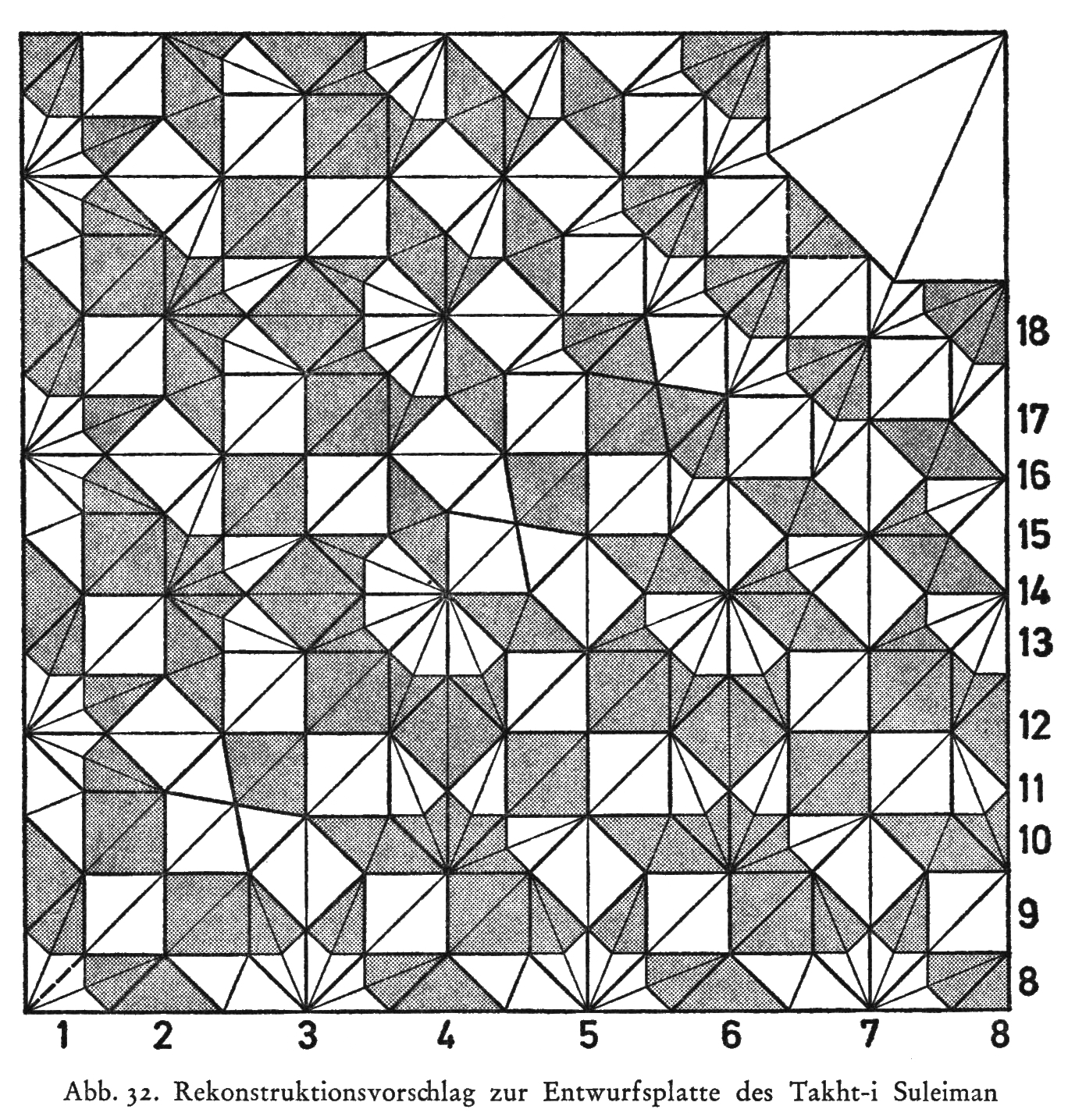

Most Ilkhanid stalactite vaults share the same geometric basis as the vault in the Southern Octagon. In their undersides, they feature identical individual forms arranged in similar or even identical ways. A sufficiently broad selection of these vaults is presented here both to clarify the assembly of the stucco elements at Takht-i Suleiman and to demonstrate all the possible combinations of these components-combinations which ultimately led to the reconstruction of the Takht-i Suleiman gypsum panel design. In addition, some of these vaults include individual elements that were not found at Takht-i Suleiman, yet clearly fit into the same geometric system.

The muqarnas vaults examined here display forms of the same geometric origin. The arrangement of the groups of elements, laid side by side and stacked atop one another, is often identical despite differing construction techniques. Two authors have attempted to understand the design processes that led to these vaults. In doing so, Herzfeld presents the "construction grid" of the Natanz mausoleum, and Notkin the "design schema" of the Shah Arab mausoleum at Shah-i Zindah. While Herzfeld's grid merely facilitates a structural survey of the vault without clarifying the design process, Notkin shows in a simplified section of the plan view shapes that precisely correspond to the design of the Takht panel.

The Design of the Stucco Panel from Takht-I Suleiman and its Reconstruction

This text is a translation of a selection of Harb's text in chapter 6.

The diagonally symmetrical arrangement of the square design suggests that it represents a quarter-dome construction. By combining four identical adjoining sections, the full dome form is obtained. Assuming the design represents a dome leads to the following conditions:

- The lower and left borders indicate the wall surfaces.

- The upper and right borders mark the intersection lines along the axes.

- The lowest point on the wall surface lies in the lower left corner.

- The highest points on the wall surfaces lie in the lower right and upper left corners, at the intersections of the axes with the wall surfaces.

- The dome apex is formed by an octagonal cloister vault.

- The uppermost elements along the axes and diagonals lie at the same height, in or just below the closing cloister vault.

- The individual horizontal stalactite rows describe broken (angled) circular arcs around the apex.

- The axes of the elements generally point toward the apex, but never away from it.

Along the wall surfaces, 3½ star-shaped forms are arranged side by side. Their diameters equal two side lengths and one diagonal of the base square. The number of these star forms, whose three-dimensional shape the designer likely envisioned, probably determined the axial spacing in the plan - that is, the axes of the dome.

The squares can be interpreted either as concave elements FA (see ) or as convex intermediate elements (see ); the rhombuses as concave elements FE (see ) or as convex intermediate elements ZE (see ), but also as intermediate elements with a long ridge arch. The triangles resting with their base on the wall surfaces can only be of type FB (see ). The star shapes in the central area of the design invite an interpretation similar to that of Natanz 2 (see ). However, it is impossible to construct even two rows of stalactites using only the elements mentioned above. Since the complete elements are insufficient to explain the structure of the vault, the designer of the panel must have also used partial elements, not shown explicitly, which can be inscribed within the existing surfaces.

Figures from Ilkhanidische Stalaktitengewölbe

One set of drawings illustrates the basic muqarnas shapes used in the Southern Octagon. The other set presents muqarnas floor plans from various other Iranian buildings.

My animations

Harb presented his reconstruction of the Southern Octagon, but his interpretation is one out of many. His drawing provides information about the shape of the tiers. However there are alternatives. My alternative design B is the same as Harb, but alternatieve design A+ is a different one. The STL viewer is an online tool that supports rotation, panning and zooming.

- Comparison Southern Octagon: Harb - Yaghan - Dold Samplonius - Harmsen

- Reconstruction of the Dome at the Gypsum Plate

My animations of the Southern Octagon

My animations of the Dome of the Gypsum Plate

Below is the animation of Harb's interpretation.

Other interpretations are on a seperate webpage: the debarte between Yaghan, Dold-Samplonius and Harmsen.

Open STL file in a new window

Open STL file in a new window