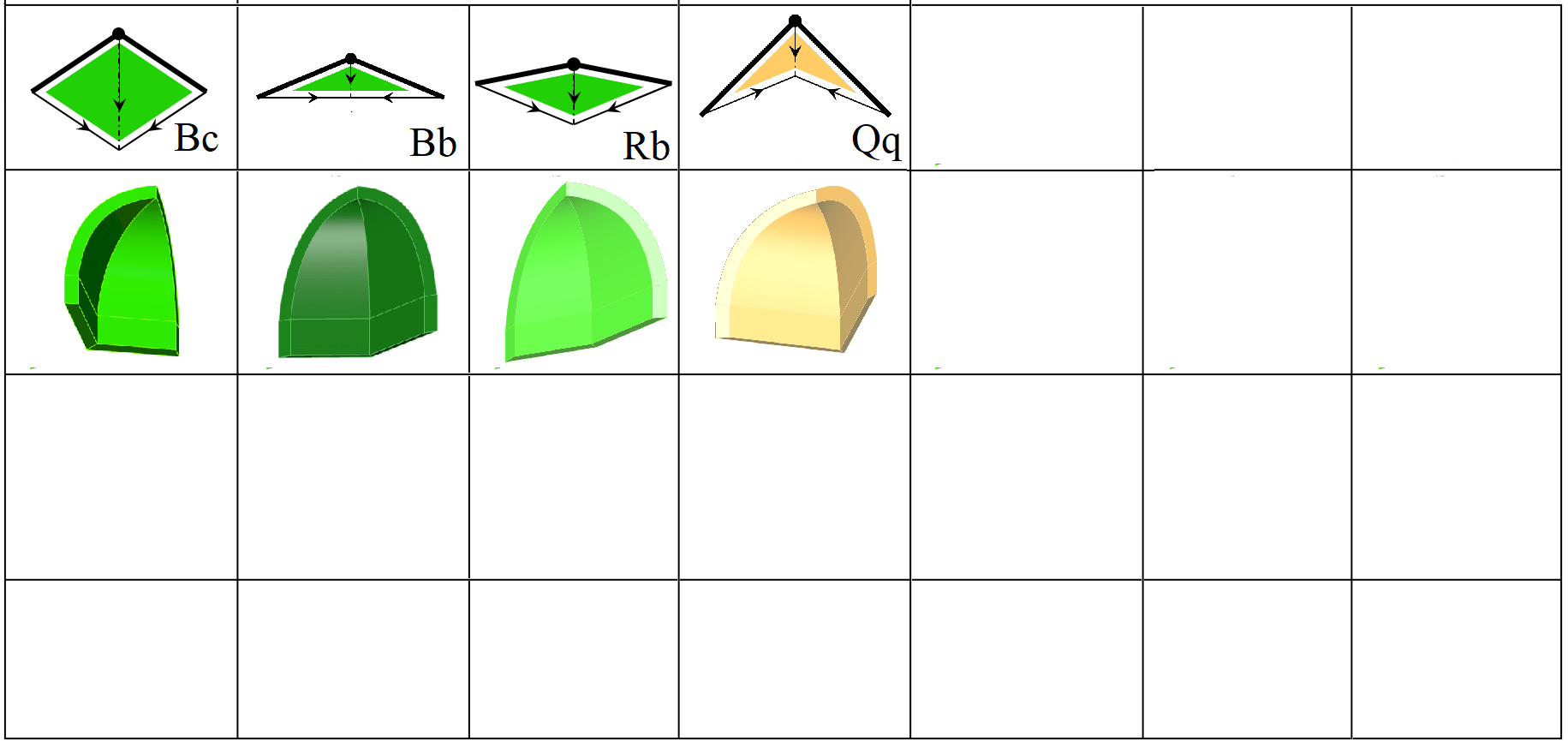

Stretching an Octagon to a Square

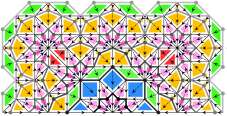

I've seen muqarnas with octagonal plans and others with rectangular or square layouts, and I began experimenting to understand the differences between these forms. One question I explored was whether an octagonal plan could be stretched into a square without affecting the upper tiers of the muqarnas. For example, take a small niche muqarnas in the Kasim Padisah Mosque in Diyarbakır. Tuncer provided a floor plan, which I checked on-site in 2022. Squaring the plan isn't too difficult: the corners are filled with small dome-like elements. I found that I could close the dome by placing two opposing base units; the intermediates K from Table 1. But in reality, these elements might be constructed differently. Similar small domed transitions appear in other buildings as well-like the Kasimiye Medrese in Mardin, as shown by Ödekan, or in the Elbasi Karatay Han in Kayseri.

- Kasim Padisah according Tuncer

- My Instagram story on squaring

- Mardin Kasimiye Medresesi according Ödekan

- Kayseri Elbasi Karatay Hani according Ödekan

Rectangular Top

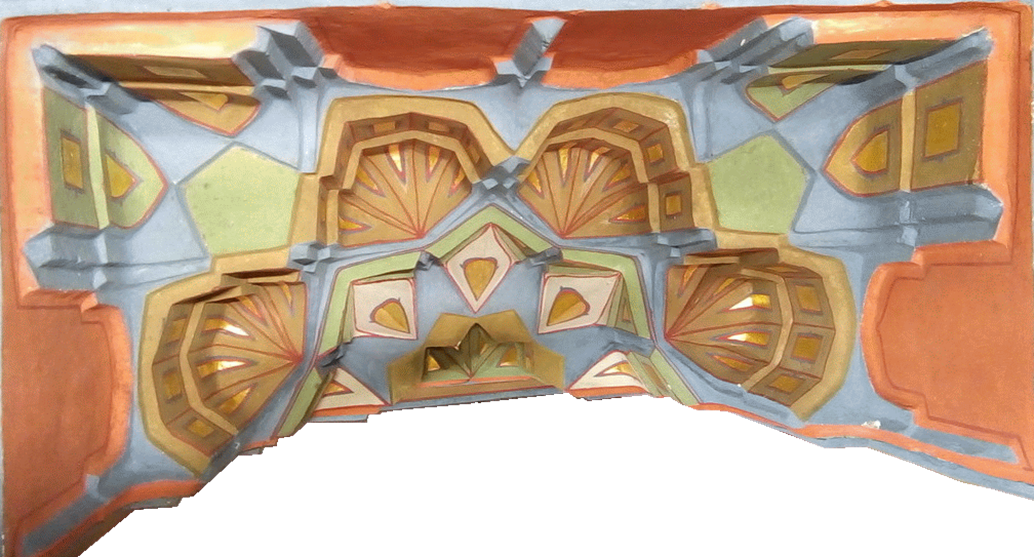

Many muqarnas feature a star-shaped pattern at the top, which is the most common way to close the structure. A rectangular second tier, however, is rare-but it can be done. A good example is the mihrab muqarnas of the Üsküdar Marmara University Theology Faculty Mosque in Istanbul. Its top tier forms a star, made of rhombuses split at a 90° angle. These rhombuses are constructed from three upper units of type T, flanked by a left half-T and a right half-T, rather than the more typical upper unit N resting on a base unit M. Only two of the T units actually form a complete rhombus-where the upper unit T rests on a base unit U. To achieve the rectangular form, the central T rests on half of a hypothetical upper unit Qn, which does not exist on its own because its 45° interior angle is too narrow. The flanking T units rest on half of a base unit I.

Fat Rhombus

In the Melek Ahmet Pasa Mosque in Diyarbakır, the third tier from the top features a rare rhombus-shaped unit. Together with the biped-shaped unit below it-in the fourth tier-it forms a kite-like composite shape, where the rhombus is the upper part and the biped is the base. Unlike a standard rhombus, which typically has 135° angles, this one has a sharper 112.5° angle. Its length is also shorter than the standard unit length, allowing it to fit against the back of the standard jug-shaped unit. The corresponding biped unit below deviates as well: instead of the usual 135° angle at the front and 90° at the back, this version has a 112.5° front angle and a 67.5° back angle. This muqarnas also shows another kind of irregularity: the top three tiers are built with smaller-scale units, while the bottom three tiers use larger ones. The tier with the broad rhombuses acts as a kind of glue, visually and structurally binding the upper and lower sections together.

Corner Stone

One of the rare parts is a corner stone, usually applied in the bottom tier. Once, I modelled the corner as the combination of a square Aand two half units F to fil the gap.. Mamoun Sakkal mentioned an alternative building block for corners that comprises the whole combination. I call it Oo.

The Bursa Hacılar mihrab muqarnas has many squares. In the corners, I need a combination of predefined building blocks, including a slightly smaller square. Here a corner stone Oo would be more appropriate.

- Bursa Harcilar

Bursa Hacilar Cami Mihrab had a restauration. The corners have a dedicated cornerstone.

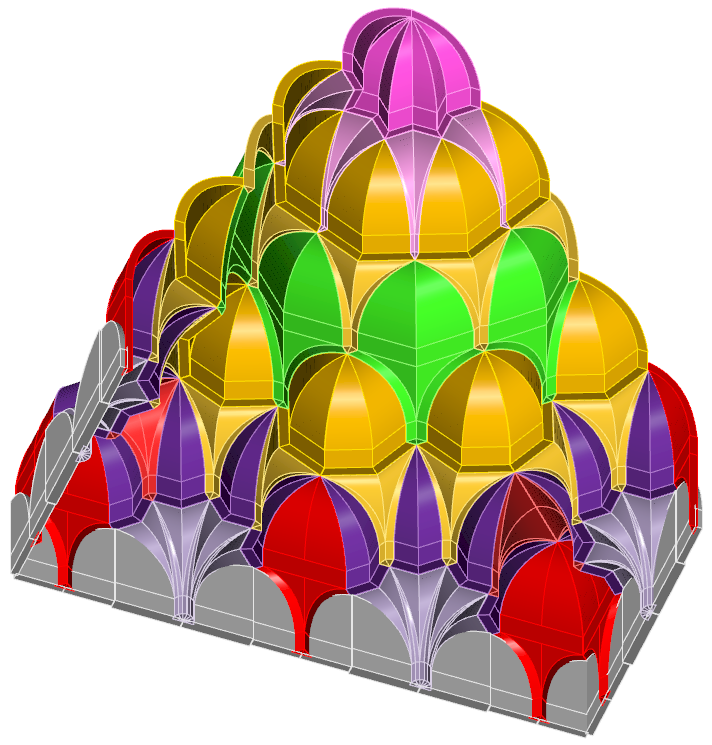

Pentagons

Muqarnas are ornamental features of Islamic architecture. Their 2D floor plans resemble tessellations of squares, rhombuses and kites. However, these plans often oversimplify the spatial complexity, losing key details. The underlying grid may be octagonal, hexagonal or decagonal, but in the larger Seljuk and Ottoman muqarnas, pentagonal or heptagonal shapes are added. Mathematically, it's impossible to fit regular pentagons or hexagons into a strict octagonal grid. Yet, muqarnas defy these constraints, blending art and geometry. For instance, the portal muqarnas of the Atik Valide Mosque in Üsküdar, Istanbul (16th-century), features pentagonal and hexagonal püskül embedded within an otherwise octagonal grid.

Tuncer's floor plans of Diyarbakır do not have pentagons, but Ödekan's thesis has examples. My favorite example is Istanbul Üsküdar Atik Valide, the 16th century Ottoman imperial mosque, designed by the architect Mimar Sinan for Nurbanu Sultan, the wife of Sultan Selim II. The portal muqarnas has both pentagons and hexagons. See also the discussion of Agirnbas ellipses.

Before the conquest of Istanbul, Bursa was the capital of the Ottoman Empire. Bursa is known for the Yesil Cami, but the Muradiye Tomb Complex is just as interesting. Although the Yesil Cami and the Muradiye Tomb Complex date from the same period, the muqarnas compositions are very different. The muqarnas of Yesil Cami are entirely in line with later Ottoman muqarnas, but those of the Tomb Complex appear somewhat clumsy in comparison.

- Grid of Ellipses for Atik Valide Mosque

- Wikipedia: Atik Valide Mosque

- Agirbas and Yildiz propose a grid of ellipses (7)

In the seventh episode, I focus on the three star patterns. I am amazed that I can't draw these stars in a rectilinear octagonal grid, but can do in an elliptical octagonal grid.

- Kayseri Kursunlu Mosque

In the next episodes, I want to discuss the construction of pentagonal and hexagonal starshapes. Now an example in Kayseri.

- Bursa Muradiye

There is a pentagon inside the octagon. Bursa Muradiye Tomb complex has interesting muqarnas

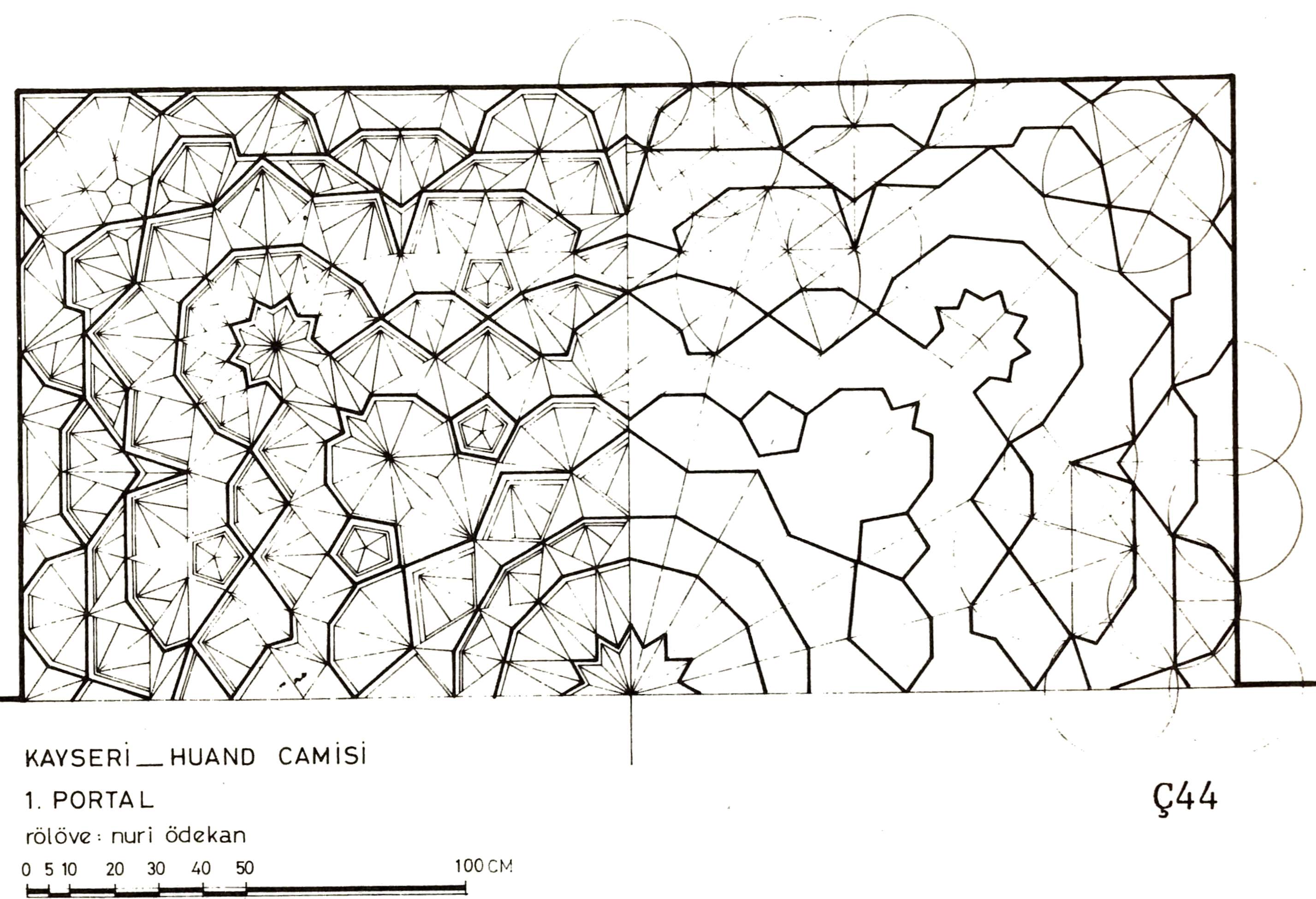

- Kayseri Elbasi Karatay Hani

This caravanserai portal muqarnas design is a combination of an octagonal grid, a decagonal grid and a hexagonal grid.